Our Common Task: Climate Protection

The total refrigerants quantity calculated in CO₂ equivalent will be reduced annually in the coming years according to a quota system.

The F-Gas Regulation restricts the use of various refrigerants. We explain the background, what you need to know about it, and how we can help you convert your cooling system.

The long predominant halocarbons (CFCs, HCFCs, and HFCs) combine good efficiency and safety with acceptable costs. But chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) also contribute to ozone depletion and hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) to global warming. In response to the atmospheric ozone layer depletion caused by CFCs and HCFCs, the Montreal Protocol mandated the phase-out of CFCs and HCFCs in 1987. This protocol has become the first multilateral environmental agreement with truly global participation. It paves the way for refrigerants with low global warming potential (LGWP) that will maximize environmental benefits.

The Genesis of the F-Gas Regulation

Since their use started in the early 1990s, HFCs have rapidly become the dominant group of fluorinated gases (F-gases). But in view of their negative impact on the climate, the HFCs have been addressed in the “Kyoto Protocol” (1997) of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions.

The objective of the first F-Gas Regulation (EC) No. 842/2006 was to contain, prevent, and thereby reduce emissions of the fluorinated greenhouse gases covered by the “Kyoto Protocol”, by mandating improved leak tightness of equipment and optimized recovery. It was effective for stationary, transport and movable equipment.

Paris Agreement

However, the savings potential of these measures was not sufficient to meet the EU’s climate targets in accordance with the emission reduction set out in the Kyoto Protocol. Therefore, after approval by the European Parliament (EP) and the Council, Regulation (EU) No. 517/2014 on fluorinated greenhouse gases and repealing Regulation (EC) No. 842/2006 was published in the Official Journal of the EU on May 20, 2014 (L150/195) which entered in force on January 1st, 2015.

In 2015, the Paris Agreement was adopted at the 21st Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC. The goal is to keep global warming well below 2°C – and to continue efforts to limit it to 1.5°C. This, of course, also applies for the hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs).

The most direct form of EU law. Once adopted, the Regulation is legally binding in the EU Member States. It is equivalent to national law.

Every member state must reach the defined targets. National authorities must adapt their laws to meet these goals.

The 2030 Climate and Energy Framework

Three key targets for 2030:

- At least 40 % cuts in greenhouse gas emissions (from 1990 levels)

- At least 32 % share for renewable energy

- At least 32,5 % improvement in energy efficiency

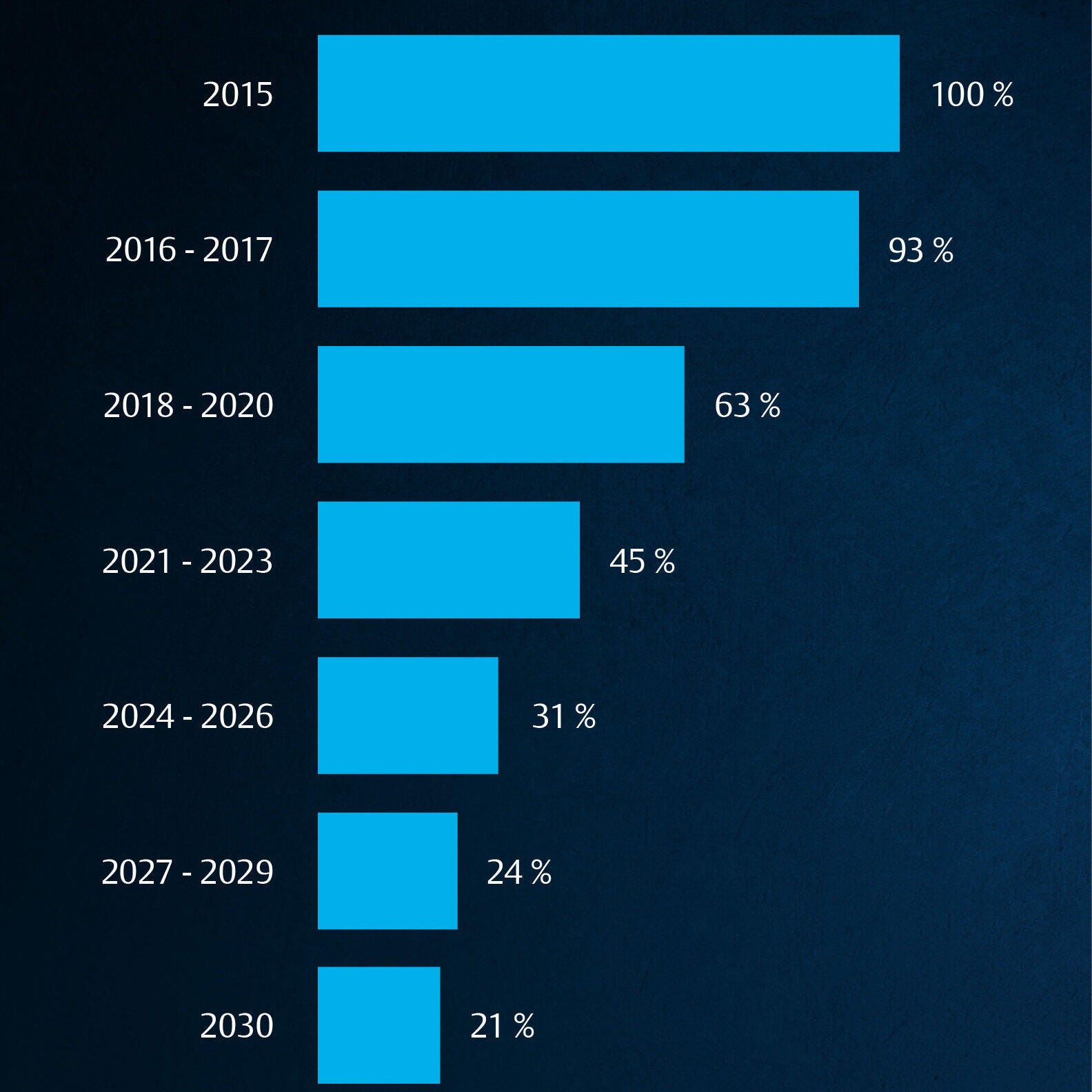

The EU Must Move On

In response to the rapid increase of greenhouse gas emissions, the 197 parties to the “Montreal Protocol” adopted the “Kigali Amendment” in 2016 to cut the production and the consumption of hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs). It entered into force on 1 January 2019. The phase down of HFC refrigerants under this amendment has the potential to avoid up to 0.1˚C of warming by 2050 and up to 0.4℃ by 2100. Global implementation of the “Kigali Amendment” would prevent up to 80 billion tons of CO₂ equivalent of emissions by 2050. With a step-by-step approach to 2030 (you see on the left). The industrialized countries started in 2019, while most developing countries will start their freeze and phase-down in 2024.

The solution for a successful and thorough phase-down of HFCs with energy efficiency benefits is to replace these substances with refrigerants having low global warming potential (LGWP). For developing countries, this means transitioning from hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFC) directly to LGWP refrigerants without taking the uneconomical and environmentally hazardous detour via HFCs with high GWP.

Representatives of the EU member states and the EU Parliament agreed on April 21, 2021, to tighten the initially defined climate target for 2030. Then the EU’s greenhouse gases are to be reduced by at least 55 percent below the 1990 level. Previously, the milestone target was a 40 percent reduction in greenhouse gases, but this is not enough to achieve climate neutrality in 2050. Then, almost all greenhouse gases are to be avoided or stored. This will require a comprehensive transformation of the economy towards renewable energies and emission-free production processes over the next 30 years.

Gradual Reduction of F-Gases

The current F-Gas Regulation 2014 (EU 517/2014), bans the usage of refrigerants with GWP above 2,500, restricts high GWP refrigerants in some applications, and introduces the phase-down of fluorinated greenhouses gases. As this is not yet sufficient, the directive is currently being revised.

The regulation has already been supplemented in many points and its application has been tightened considerably. A major change is the evaluation of a system according to the global warming potential (GWP) and the filling quantity (kg) in the system. The product of these factors is referred to as the “CO₂ equivalent” and is the decisive parameter for evaluating a refrigeration system, for leak checks, and service refilling.

Required is the reduction of leakage by all technically and economically feasible measures. With a refrigerant charge of 5 tons or more of CO₂ equivalent, a refrigeration system must be leak tested. Excluded are hermetically sealed systems with a quantity of less than 10 tons of CO₂ equivalent.

Much Stricter Rules

Compared to 2006 F-Gas regulation the 2014 version (EU 517/2014) demands stricter rules on refrigeration systems containing fluorinated greenhouse gases with regard to

- regular leak inspections

- fluid recovery

- trainings

Reduction of Refrigerants

Since January 1st, 2020, the use of fluorinated greenhouse gases with a global warming potential of 2,500 is prohibited in new refrigerating system. In addition, these refrigerants are banned for service or maintenance in systems with a refrigerant charge of 40 tons or more CO₂ equivalent. In practice, this concerns the refrigerant R404A. Reprocessed or recycled refrigerant may still be used until January 1st, 2030, provided it comes from the same plant.

The key element for phasing down HFC consumption is refrigeration and air conditioning technologies that use truly sustainable alternatives such as natural refrigerants like ammonia (NH3), carbon dioxide (CO₂), and hydrocarbons (HCs). These refrigerants with very low global warming potential (LGWP) maximize environmental benefits. Natural refrigerants are gaining importance as an effective long-term solution for many applications, where gaps of cost, energy efficiency, and safety requirements have been addressed.

To Reduce Carbon Footprints

We offer the widest range of refrigeration compressors on the market, allowing the use of multiple technologies and refrigerants. We are committed to supporting solutions that safeguard food and protect the environment. Our key environmental objectives are to minimize the impact of climate change by using energy responsibly and reducing carbon footprints – both for us and for our clients.

Prevention of Emissions

The use of refrigerants will change drastically over the next 15 years. High GWP variants (like R404A, R410A) will almost completely disappear from the market. In 2030, the choice will be limited to natural refrigerants or other low GWP options. CO₂ will be the means of choice in many applications due to its many advantages. Especially now that we have succeeded in using it in transcritical applications – with the new Copeland CO₂ transcritical scroll technology.